This is the second part in the Reality# series that adds to the conversation about David Chalmers’ book Reality+

Virtual and Possible Worlds

A dream world is a sort of virtual world without a computer. (Chalmers, p.5)

Simulations are not illusions. Virtual worlds are real. Virtual objects really exist. (Chalmers, p.12)

Many people have meaningful relationships and activities in today’s virtual worlds, although much that matters is missing. Proper bodies touch, eating and drinking, birth, and death, and more. But many of these limitations will be overcome by the fully immersive VR of the future. In principle, life in VR can be as good or as bad as life in a corresponding non virtual reality. Many of us already spend a great deal of time in virtual worlds. In the future, we may well face the option of spending more time there, or even of spending most or all of our lives there. If I’m right, this will be a reasonable choice. Many would see this as a dystopia. I do not. Certainly, virtual worlds can be dystopian, just as the physical world can be. (…) As with most technologies, whether VR is good or bad depends entirely on how it’s used. (Chalmers, p.16)

Computer simulations are ubiquitous in science and engineering. In physics and chemistry, we have simulations of atoms. And molecules. In biology we have simulations of cells and organisms. In neuroscience, we have simulations of neural networks. In engineering we have simulations of cars, planes, bridges and buildings. In planetary science, we have simulations of Earth climate over many decades. In cosmology, we have simulations of the known universe as a whole. In the social sphere, there are many computer simulations of human behavior (…) In 1959. The Symbol Metrics Corporation was founded to simulate and predict how our political campaigns messaging would affect various groups of voters. It was said that this effort had a significant effect on the 1960 U.S. presidential election. The claim may have been overblown, but since then social and political simulations have become mainstream. Advertising companies, political consultants, social media companies and social scientists build models and run simulations of human populations as a matter of course. Simulation technology is improving fast, but it’s far from perfect. (Chalmers, p.22)

In the actual world, life developed on Earth, yet Chalmers proposes possible worlds where the solar system never came into existence. He goes even further by suggesting possible worlds where the Big Bang never occurred. I find this line of reasoning highly doubtful. In my view, Chalmers uses the term ‘possible’ too liberally. What does it mean to assert that there is a possible world where no universe evolved? Such a proposition appears to stretch the boundaries of our language to its limits.

It seems to me that David Chalmers is overreaching when he talks about ‘possible worlds’. This notion of possibility is already present in his earlier works like “The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory” (1996).

Chalmers then used the concept to discuss modal realism, the idea that other possible worlds are as real as the actual world. This was a radical departure from the more common view, known as actualism, where only the actual world is considered truly real.

One of the key use Chalmers makes of possible worlds was in relation to his concept of “zombie worlds”. These are worlds physically identical to ours, but where no inhabitants are conscious. They behave as if they were conscious, but there’s no subjective experience – hence, they are “zombies”. The possibility of such a world is used by Chalmers to argue for the hard problem of consciousness: the question of why and how physical processes in the brain give rise to subjective experiences.

Look at how our language can produce true horrors if we do not use the subjunctive mood properly:

1. I wish I were not so good at being terrible.

2. If only I were someone else who is not me.

3. I wish I didn’t hope for impossible dreams.

4. If only I were less optimistic about my pessimism.

5. I wish I were not so unsure about my certainty.

Chalmers’ notion of possible universes seems to allow for universes were all the possibilities expressed in the sentences above would have a non-zero probability of becoming true.

1. If there were a possible universe where everything is certain, nothing would be uncertain.

2. In a possible universe where contradictions are possible, the concept of possibility becomes impossible.

3. If there were a possible universe with no limitations, the idea of possibility itself would be limited.

4. In a possible universe where all possibilities are realized, there would be no room for the possibility of impossibility.

5. If there were a possible universe where everything is impossible, the concept of possibility would lose its meaning.

What does it mean to simulate an impossible universe?

Flawed classifications

Chalmers discusses the concept of pure, impure, and mixed simulations. Neo from the movie, The Matrix, is an impure sim because his mind is not simulated. However, The Oracle is a pure sim because her mind is part of the simulation. These are two different versions of the simulation hypothesis. We could be bio-sims connected to the Matrix, or we could be pure sims whose minds are part of the Matrix.

The addition of a third category, ‘mixed simulations’, confuses me as it seems identical to an ‘impure simulation’; it’s not even a special case. Furthermore, the specific scenario where a simulation contains only bio-systems, which could arguably be considered a ‘pure impure simulation’, isn’t even mentioned.

This classification system is very confusing. His definitions of ‘global’ and ‘local’ simulations also need improvement. His distinctions like ‘temporary’ and ‘permanent’ simulations, ‘perfect’ and ‘imperfect’ simulations reveal more about our use of language than they do about the utility of these simulation categories.

In my opinion, a better way to label these types would be as closed simulations (all the subjects and objects participating in a simulation are contained inside the simulation; there are only NPCs, for example) and open simulations (organic bio-sims can participate and inhabit digital avatars, but in most cases, there will always be synthetic subjects to enrich the simulation). Tertium non datur. There isn’t a third category that is both open and closed, every possible simulation is contained within these two sets.

Could simulations be the most difficult human phenomenon to describe efficiently with mathematical set theory? We know from history how Gödel’s demolition of set theory ultimately shattered the dreams of Russell and Whitehead to come up with a perfect mathematical system.

If a simulated brain precisely mirrors a biological brain. The conscious experience will be the same. If that’s right, then just as we can never prove we are not in an impure simulation, we can also never prove that we are not in a pure simulation.(Chalmers, p.34)

It appears as though David Chalmers is unfamiliar with concepts such as chaos theory, Lorenz attractors, dynamic systems, the butterfly effect, and so on. If there were beings capable of willingly switching between simulation levels, they would likely lose all sense of direction, in terms of what is up and what is down. This disorientation is similar to what avalanche survivors or deep-sea explorers might experience. Up and down become meaningless concepts.

This situation is touched upon in the movie “Inception,” where one of the main characters believes that what we call ‘base reality’ is just another level of a dream world and attempts to escape the simulation through suicide.

Does our consciousness has a sort of gravitational pull that prevents us from being fully immersed in realities that are not the reality into which we were born – our mother reality, so to speak? And could the motion sickness that we get from VR, if we are immersed in it for too long, be a bodily sensation of this alienation effect? Could our need for sleep indicate that we do not belong here? Should evolution in the long term not favor species that don’t require rest? Resting and sleeping makes any animal maximal vulnerable to its environment, it is also useless for procreation.

Pseudoqualifying Attributes

A plethora of problems with Chalmers’s argument stems from the fact that he doesn’t seem to be aware of how he uses certain attributes. There’s a class of attributes in our language that can be described as ‘blurred’. When we examine them closely, we can momentarily imagine them as being sharper than they really are. What does it mean to assign a precise value to Pi? While the statement seems reasonable in natural language, someone familiar with the concept of irrational numbers would point out the error.

I argue that words like ‘perfect’, ‘imperfect’, ‘pure’, ‘impure’, ‘precise’, and so on, belong to a category of pseudo-binary attributes in our language. In our minds, we often add qualifiers like ‘enough’ at the end of these attributes. Using such words can be a mental shortcut but it’s potentially misleading.

Consider a sentence from page 35: “A perfect simulation can be defined as one that precisely mirrors the world it’s simulating.” At first glance, this sentence appears sound. But upon close inspection, the contents of this sentence, especially the use of the word ‘mirroring’, become questionable. In our daily language, ‘mirroring’ can have a visual meaning, like the reflection we see in a mirror. But a reflection isn’t identical to the original object – it’s an inversion. So, what does it mean for a reflection to be imperfect or to mirror imprecisely?

Let’s imagine a skilled actor imitating our movements in front of a mirror, providing the perfect illusion that we are seeing our own reflection. An imperfect mirror might occur if the actor misses one of our micro expressions or is too slow to mimic our actions, revealing the illusion. This is what I believe Chalmers is hinting at with his terminology.

Moreover, even a genuine reflection is not a ‘perfect’ reflection. The time it takes for the light rays to travel from my eyes to the mirror, and then to my retina and into my visual system, results in a delay. The synchronicity of my movements and my reflection is an illusion conveniently overridden by our brain.

This is analogous to the illusion that our vision is steady, continuously gathering information, while in truth our eye movements are sporadic. It’s more convenient for our brain to ignore these discontinuities. We also never notice the blind spot in our visual field that our brain fills.

In this category also fall the tendency in philosophy to label things like problems and philosophy schools with descriptive adjectives like hard and strong.

“This the hard problem of consciousness”.

“He is a strong Idealist.”

“This is a weak argument.”

There is even a range of objects that are a real pain to discuss: Holes. Holes are widely considered a bad thing to have Argumentations can have holes. Black holes warp Reality. Is a hole even a real thing? In the field of topology, the term “genus” refers to a property of a topological space that captures an intuitive notion of the number of “holes” or “handles” a surface has. It’s a key concept in the classification of surfaces. So, if Math says so, it must be real.

Our language permits sentences such as, “He removed the hole from the wall.” A hole is a thing that can be measured but not weighed. Many intuitive assumptions falter when faced with the reality that everyone is familiar with holes, and everyone has created holes, yet there is nothing tangible to show for it.

The Digital Mind Illusion, a psychological experiment

The Digital Mind Illusion, a psychological experiment

The Rubber Hand Illusion (RHI) is a well-known psychological experiment that investigates the feeling of body ownership, demonstrating how our perception of self is malleable and can be manipulated through multisensory integration.

In the illusion, a person is seated at a table with their left hand hidden from view, and a fake rubber hand is placed in front of them. Then, both the real hand and the rubber hand are simultaneously stroked with a brush. After some time, many people start to experience the rubber hand as their own, they feel as if the touch they are sensing is coming from the rubber hand, not their real one. This illusion illustrates how visual, tactile, and proprioceptive information (the sense of the relative position of one’s own parts of the body) can be combined to alter our sense of bodily self.

The implications of RHI for theories of consciousness are profound. It demonstrates that the perception of our body and self is a construction of the brain, based not only on direct internal information but also on external sensory input. Our conscious experience of our body isn’t a static, fixed thing – it’s dynamic and constantly updated based on the available information.

One influential theory of consciousness, the Embodied Cognition Theory, suggests that our thoughts, perceptions, and experiences are shaped by the interaction between our bodies and the environment. The RHI experiment supports this theory by showing how altering sensory inputs can change the perception of our body.

Furthermore, the Rubber Hand Illusion has been used to explore the neural correlates of consciousness – which parts of the brain are involved in the creation of conscious experiences. Studies have shown that when the illusion is experienced, there is increased activity in the premotor cortex and the intraparietal sulcus – areas of the brain involved in the integration of visual, tactile, and proprioceptive information.

Overall, the RHI demonstrates the malleability of our conscious experience of self, supports theories of consciousness that emphasize the role of multisensory integration and embodiment, and helps to identify the neural correlates of these conscious experiences. (…)

The Rubber Hand Illusion (RHI) experiment, and similar experiments like it, highlight that our sense of reality, at least on the level of personal bodily experience, is not purely an objective reflection of the world. Instead, it’s a construct based on sensory information being processed by our brains.

We’re nearing a point where rudimentary mind-reading devices, once trained on an individual’s brain, can provide approximations of our thoughts. Consider a scenario where we create an identical digital twin of a person that mirrors the actions of the original individual. We then show the person a live image of themselves and their digital twin side by side. Given our basic mind-reading capabilities, we ask the person to think about one of 3 specific animals. However, we don’t reveal our ability to read their mind.

Whenever the individual thinks of an animal, we project an image of that animal above the heads of both individuals in the experiment. Above the actual person, we display the corresponding animal, while above the simulated person, we show a different animal.

In the beginning the Actual Mirror image gets more answers right than the Sim, but this changes over time. We also pretend that we need the Test person to press a button to confirm if our guess is right.

Every time the digital twin correctly identifies the animal, the person presses a button. This way, we create a scenario where we monitor their reactions without explicitly revealing our mind-reading capabilities.

In the first phase of the experiment, we gradually lead the person to believe that they are the simulated individual’s twin. Then, we gradually lower the room temperature. As a result, sweat becomes visible on the simulated person’s forehead. Now, the crucial question arises: What happens with the actual person? Do they also start to sweat? Is there a possibility of experiencing reality/motion sickness due to the inconsistency between the decreasing room temperature and the visual cues (the simulated person sweating)?

If the test subject fully embraces the idea that their identity is embodied in the simulated individual, the subsequent step would be to investigate whether the simulated person can influence the actual person’s thoughts. For instance, if the actual person thinks of a lion, but we display an antelope above the simulated person’s head, will the actual person start to doubt their own thoughts and become convinced that they were actually thinking of an antelope?

The Rubber Hand Illusion (RHI) findings suggest that the brain does not possess any unique conscious qualities compared to the rest of the central nervous system.

One could envision a range of experiments akin to the renowned Asch conformity experiments. The fundamental inquiry in these scenarios is how to immerse the brain in the simulation to such an extent that it begins to question its own thoughts and intentions without even needing a highly detailed VR equipment.1

True Story

What does it mean to say a story is true? It implies that the events described in the story actually happened in the real world, not in a fictional one. True stories are based on factual events, and therefore, only true stories can be false. For example, a story about Santa Claus cannot be false because Santa Claus himself is not real.

This notion of reality differs from what Chalmers suggests when he says, “Santa Claus and Ghosts are not real, but the stories about them are.” Chalmers seems to view reality in a different context, acknowledging that certain stories can be fictional, even if they contain elements that are not real.

Imagine a sorting machine that could distinguish the real parts of a story from the fictional ones in a book. To make this distinction, a reference table called ‘Human History’ would be needed. This table would allow us to compare the contents of the book with trusted sources to verify their authenticity.

Chalmers proposes five criteria to test if something is real:

1. It exists.

2. It has causal power or the ability to cause something else to happen; it works.

3. It adheres to Philipp K. Dicks Dictum, meaning reality persists even if one stops believing in it. It is not influenced by the mind that perceives it.

4. It appears roughly as it seems.

5. It is genuine, adhering to Austin’s dictum.

Chalmers acknowledges that these criteria themselves are vague and blurry. He speculates that some things may have a degree of reality, meaning the more criteria they meet, the more real they are. However, this concept can be somewhat disappointing, as it introduces definitions that lead to other complex philosophical questions.

Considering all aspects, it’s surprising that Chalmers never fully embraces the concept of continuous reality values. Reality seems to exist on a fuzzy spectrum with gradual values. For instance, something could be 80% real depending on how well it meets the listed criteria. This leads to uncertainty, making it difficult for two human brains to reach a unanimous agreement on what the term ‘real’ truly means.

The concept of suffering

The primary goal of any scientific simulation is to provide an opportunity to experience the outcomes without enduring their real-life consequences. Reality, for sentient beings, is a simulation that elicits genuine suffering. It is peculiar that in a book arguing for Simulationrealism, no glossary entry is devoted to the concept of suffering, though Chalmers does touch on morals and ethics.

Our experiences reveal that even in our present imperfect simulations, genuine suffering already exists. Consider multiplayer games: when your avatar is repeatedly killed, you feel authentic anger and frustration. If a member of your raiding party receives their 10th legendary item while you receive none, you feel real jealousy. You might argue that when your avatar is shot in the head in Call of Duty, you survive physically, but the frustration this event causes might increase global suffering more than if a real-life headshot were to instantly end your suffering.

The philosopher of science Karl Popper insisted that the whole mark of a scientific hypothesis is that it is falsifiable, meaning it can be proven false using scientific evidence. However, the simulation hypothesis we’ve encountered is not falsifiable since any evidence against it could potentially be simulated. As a result, Popper would argue that it does not qualify as a scientific hypothesis.

Many contemporary philosophers share the view that Popper’s criterion is excessively stringent. There exist scientific hypotheses, such as those concerning the early universe, that may never be falsified due to practical limitations. Despite this, I am inclined to believe that the simulation hypothesis falls outside the realm of a strictly scientific hypothesis. Instead, it lies in the intersection of the scientific and philosophical domains.

Certain versions of the simulation hypothesis can be subject to empirical tests, allowing them to be examined through scientific means. However, there are other versions of the hypothesis that are inherently impossible to test empirically. Regardless of their testability, the simulation hypothesis remains a meaningful proposition concerning our world. (Chalmers p.38)

I don’t think Chalmers achieves something in this paragraph. To say that something is partly scientific and partly philosophical diminishes the philosophical part. It’s like saying the Bible is partly historical and partly fictional. Some of the events contained in the book can be proven or disproven with historical records, like the Exodus from Egypt, historical persons like King David or Pontius Pilate, or even Jesus from Nazareth. However, that would not be enough for true believers who insist that all the magic and wonder described in the book is real or was real. They truly believe that Jesus resurrected from the grave and walked on water. This is why it’s futile to even use scientific methods to deal with all the holy scriptures; it’s a waste of time because the essence of the belief system described in these pages does not accept the scientific method. So, no, the parts of the simulation hypothesis that would be testable are not the interesting ones. At the core of the simulation hypothesis lies a philosophical argument, not a scientific one. Science is at the periphery.

Knowledge and Skepticism

A common view of knowledge, going back to Plato, is that knowledge is justified, true belief. To know something, you have to think it’s true (that’s belief) you have to be right about it (that’s truth) and you have to have good reasons for believing it (that’s justification). (Page 44)

In philosophy, a skeptic is someone who casts doubt on our beliefs about a certain domain(…) The most virulent form of skepticism is global skepticism casting doubt on all of our beliefs at once. The global skeptic says that we cannot know anything at all. We may have many beliefs about the world, but none of them amount to knowledge. (Page 45)

The simulation hypothesis may once have been a fanciful hypothesis, but it is rapidly becoming a serious hypothesis. Putnam put forward his brain-in a-vat idea as a piece of science fiction. But since then, simulation and VR technologies have advanced fast, and it isn’t hard to see a path to full scale simulated worlds in which some people could spend a lifetime. As a result, the simulation hypothesis is more realistic than the evil demon hypothesis. As the British philosopher Barry Dainton has put it the threat posed by simulation skepticism is far more real than that posed by its predecessors. Descartes would doubtless have taken today’s simulation hypothesis more seriously than his demon hypothesis, for just that reason. We should take it more seriously too.(Page 55)

Bertrand Russell once said the point of philosophy is to start with something so simple as not to seem worth stating, and to end with something so paradoxical that no one will believe it. (Page 56)

To doubt that one is thinking is internally inconsistent: The doubting itself shows that the doubt is wrong. (Page 59)

No Objections from me here, this whole part is very well put together.

Idealistic Contradiction

We’ve already touched on one route to the conclusion that the hypothesis is contradictory, suggested by Berkeley’s idealism. Idealism says that appearance is reality. A strong version of idealism says that when we say, “we are in a simulation,” all this means is “it appears that we are in a simulation” or something along those lines. Now the perfect simulation hypothesis can be understood as saying: “We are in a simulation, but it does not appear that we are in a simulation.” If the strong version of idealism is true, this is equivalent to “We are in a simulation and we are not in a simulation” which is a contradiction. So, given this version of idealism, we can know that the simulation hypothesis is false. (Chalmers, p.75)

Reality is what our minds prioritize over imaginary things.

Reality is what Evolution forces (up)on us.

Simulations are what we invent to slow down and cushion the freight train of the impact of evolutionary pressure.

Reality is that which can’t be skipped.

When MLK says in front of a crowd fully conscious: Ï have a dream… does that make his whole speech not very unbelievable? No – you see he uses dream as a metaphor for seeing in the future. A prophetic dream he wishes to become reality.

What is reality?

Virtual things are not real is the standard line on virtual reality. I think it’s wrong. Virtual reality is real that is, the entities in virtual reality really exist. My view is a sort of virtual realism.(…) As I understand it, virtual realism is the thesis that virtual reality is genuine reality call mom with emphasis especially on the view that virtual objects are real and not an illusion. In general realism is the word philosophers use for the view that something is real. Someone who thinks morality is real is a moral realist. Someone who thinks that colors are real is a color realist. By analogy someone who believes that virtual objects are real is a virtual realist. I also accept simulation realism: if we are in a simulation, the objects around us are real and not an illusion. Virtual realism is a view about virtual reality in general, while simulation realism is a view specifically about the simulation hypothesis. Simulation realism says that even if we’ve lived our whole life in a simulation, the cats and chairs in the world around us really exist. They aren’t illusions; things are as they seem. Most of what we believe in the simulation is true. They are real trees and real cars New York Sydney Donald Trump and Beyoncé are all real. (…) when we accept simulation realism, we say yes to the reality question. In a simulation, things are real and not illusions. If so, the simulation hypothesis and related scenarios no longer pose a global threat to our knowledge. Even if we don’t know whether or not we’re in a simulation, we can still know many things about the external world. Of course, if we are in a simulation the trees and cars and Beyoncé are not exactly how we thought they were. Deep down, there are some differences. We thought that trees and cars and human bodies were ultimately made of fundamental particles such as atoms and quarks instead they are made of bits. I call this view virtual digitalism. Virtual digitalism says that objects in virtual reality are digital objects roughly speaking comma structures of binary information comma obits virtual digitalism is a version of virtual realism since digital objects are perfectly real. Structures of bits are grounded in real processing, in a real computer. If we are in a simulation, the computer is in the next World up, metaphorically speaking. But the digital objects are no less real for that. So, if we are in a simulation the cats, trees, and tables around us are all perfectly real. (Chalmers, p.105)

Chalmers appears to intend a synthesis of Idealism and Realism. His usage of ‘realism’ seems clear, yet he subtly stumbles when stating, “if we are in a simulation …things are not exactly how we thought they were.” (Here, substituting ‘exactly’ with ‘really’ swiftly muddies the clarity he had been striving to maintain). I don’t perceive Chalmers as deliberately evasive; his efforts to preserve the concept of reality, even within a potential simulation, strike me as somewhat desperate. His argument ultimately leans more toward theology than philosophy. The key distinction between a conman and a true believer in pseudo-realities lies in the targeted sphere of control: the former aims to manipulate others, while the latter seeks self-control. In this context, Chalmers emerges as a true apostle. From there, his later construction of a Simulation Theology in the book follows logically.

Chalmers heavily burdens terms such as ‘Reality’, ‘Illusion’, and ‘Virtuality’, perhaps hoping that this semantic shock treatment will jolt us into a new perspective.

The Big Swap

Imagine a scenario where, following birth, every infant is unknowingly separated from their biological mother and swapped with another child. Each person is raised by strangers they consider their parents, and these adoptive parents, also none the wiser, accept the child as their own. In Chalmers’ interpretation of this hypothetical situation, he might propose the idea of ‘Relationship Realism’. He would argue that since everyone involved treats each other as their real family, then they effectively are their real family. Chalmers might even extend this reasoning to suggest that even if genetic testing were to reveal that the individuals, we believed to be our parents are not our biological parents, they are still, in essence, our real parents. They might not be exactly what we initially believed, but the love exchanged between us makes this relationship real.

Imagine a scenario where, following birth, every infant is unknowingly separated from their biological mother and swapped with another child. Each person is raised by strangers they consider their parents, and these adoptive parents, also none the wiser, accept the child as their own. In Chalmers’ interpretation of this hypothetical situation, he might propose the idea of ‘Relationship Realism’. He would argue that since everyone involved treats each other as their real family, then they effectively are their real family. Chalmers might even extend this reasoning to suggest that even if genetic testing were to reveal that the individuals, we believed to be our parents are not our biological parents, they are still, in essence, our real parents. They might not be exactly what we initially believed, but the love exchanged between us makes this relationship real.

In a similar fashion, Chalmers seems to skirt around the fact that discovering my dad isn’t my biological father doesn’t provide any meaningful insights. Since I’ve been living a perfect simulation of a relationship with my non-biological parents from birth, they aren’t fake parents but my real ones. It’s noteworthy that this exercise of redefining and overloading reality-related terms is amusing only when observed from an outsider’s perspective. However, if Chalmers were to wake up tomorrow to discover his memories of being a renowned Australian philosopher authoring a book on realities and simulations were fabricated, and that he is actually within a simulation machine running a program on his digital brain, I doubt he would find it amusing.

Sisyphosical Zombies

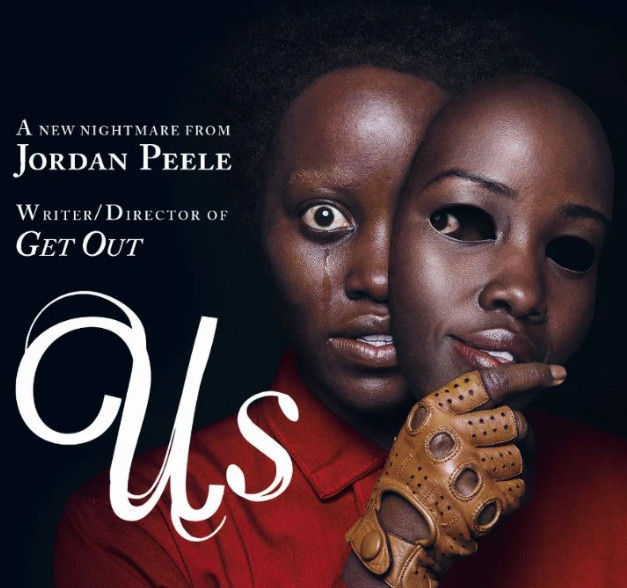

“Us” is a psychological horror film directed by Jordan Peele. The movie follows the story of the Wilson family, who encounter a group of doppelgängers that look exactly like them but possess sinister intentions. The family is forced to confront their own dark past as they fight to survive against their menacing and terrifying counterparts. As the night progresses, chilling secrets unravel, leading to a shocking revelation about the true nature of these doppelgängers and the disturbing connection they share with the family.

The movie perfectly unhinges the viewer’s sense of reality and how the concept relates to self and identity. It also questions our notions of self-control and free will.

The doppelgängers are referred to as “The Tethered.” The explanation for how The Tethered are created is left somewhat ambiguous and open to interpretation. However, it is suggested that The Tethered are the result of a secret government experiment gone wrong.

The film implies that the government sought to control the population by creating clones of individuals and keeping them confined in underground facilities. These clones, The Tethered, are physically identical to their above-ground counterparts but are forced to live in dark and oppressive conditions, mirroring the lives of their counterparts above.

Over time, The Tethered develop their own consciousness and a deep sense of resentment and desire for revenge against their surface-dwelling counterparts. They eventually rise to the surface and initiate a violent confrontation with their doubles, seeking to take their place in the world.

Now lets slightly change the parameters of the setting an instead of mindless zombies that are aimlessly walking around in tunnels below the surface, each doppelgänger is remotely connected with a VR to its Surface-Counterpart. They experience everything through the sensory input of their twins, from birth do the deathbed.

In the essay “The Myth of Sisyphus” Albert Camus explores the concept of the absurd, using the Greek myth of Sisyphus as a metaphor. Sisyphus was punished by the gods and condemned to roll a boulder up a hill, only to watch it roll back down, repeating this task for eternity.

Camus argues that even in the face of a seemingly meaningless and repetitive existence, Sisyphus can find happiness by embracing the absurdity of his situation. Despite the futility of his efforts, he can create his own sense of purpose and meaning in the act of defiance against the absurdity of life. Thus, Camus suggests that true happiness can be found in accepting and embracing life’s absurdities rather than searching for ultimate meaning or purpose.

The last sentence of the essay is:

“One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

In a twist that reminds of the great Camus Chalmers basically states:

“One must imagine Simulation real.”

However, unlike the existentialist Camus who acknowledges the absurdity of such a statement and yet tries to emotionally cope with it, Chalmers attempts to reason his way out and, in my opinion, fails.

The life of the VR-Doppelgänger according to Chalmers is no second-class reality. If it is a perfectly fine simulation worth living.

I call this new philosophical Zombie, a sisyphosical Zombie: a Zombie that is happy about lacking emotions.

- Some months later I found this experiment described, which makes a strong argument, that we are neurobiologically primed to be easily fooled by external stimuli in believing that some decision is our own will, when it is demonstrably not:

Psychophysics reveals that consciousness does not direct most actions, but instead processes reports of them, from unconscious units that do the work. Using a technique known as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), it is possible to stimulate the left or right brain motor centers in a subject’s brain, at the experimenter’s discretion. A properly sculpted TMS signal to the right motor center will cause a twitch of the left wrist, while a properly sculpted TMS signal to the left motor center will cause a twitch of the right wrist. Alvaro Pascual-Leone used this technique ingeniously in a simple experiment that has profound implications. He asked subjects, upon receiving a cue, to decide whether they wanted to twitch their right or their left wrist. Then they were instructed to act out their intention upon receiving an additional cue. The subjects were in a brain scanner, so the experimenter could watch their motor areas preparing the twitch. If they had decided to twitch their right wrist, their left motor area was active; if they decided to twitch their left wrist, their right motor area was active. It was possible, in this way, to predict what choice had been made before any motion occurred. Now comes a revealing twist. Occasionally Pascual-Leone would apply a TMS signal to contradict (and, it turns out, override) the subject’s choice. The subject’s twitch would then be the one that TMS imposed, rather than the one he or she originally chose. The remarkable thing is how the subjects explained what had happened. They did not report that some external force had possessed them. Rather, they said, “I changed my mind.”

Wilczek, Frank (2021-01-11T22:58:59.000). Fundamentals: Ten Keys to Reality (English Edition).

. ↩︎